•…Continued from Portrait of a Lady (2).

Myth: The Mona Lisa was originally of a wider dimension.

On the rocks. It has been the belief that the Mona Lisa was made smaller through tampering, not when it was stolen from the Louvre in 1911, as some would think, but long before that. Unlike Rembrandt’s Night Watch, which was also reduced in size at some point, Leonardo’s lady may have been substantially affected by the alteration. According to the apocrypha, when the painting left the artist’s hands, it had columns on both sides, which made plain that the subject was seated on a balcony and not among the rocks, as is now seen. Part of the panel comprising the columns at both sides would seem to have been cut away for some still undetermined reason, causing even Walter Pater, the writer-critic who gave the most famous description of the Mona Lisa, to make an apparent error. The elimination of the columns has highlighted the mystery of the background and contributed to the allure of the painting, though the effect is one that Leonardo might never have intended.

On the rocks. It has been the belief that the Mona Lisa was made smaller through tampering, not when it was stolen from the Louvre in 1911, as some would think, but long before that. Unlike Rembrandt’s Night Watch, which was also reduced in size at some point, Leonardo’s lady may have been substantially affected by the alteration. According to the apocrypha, when the painting left the artist’s hands, it had columns on both sides, which made plain that the subject was seated on a balcony and not among the rocks, as is now seen. Part of the panel comprising the columns at both sides would seem to have been cut away for some still undetermined reason, causing even Walter Pater, the writer-critic who gave the most famous description of the Mona Lisa, to make an apparent error. The elimination of the columns has highlighted the mystery of the background and contributed to the allure of the painting, though the effect is one that Leonardo might never have intended.

However, art historians like Martin Kemp insist the painting  has not been altered, and that the columns depicted in alleged copies of the original were added by the copyists themselves. In 2004-05 an international team of 39 specialists confirmed Kemp’s view after undertaking ‘the most thorough examination of the Mona Lisa ever’. They discovered that the frame covered an unpainted strip around all four edges of the panel, leaving the gessoed, or painted, portion untouched. The bare strip (called the ‘reserve’), which was likely to have been as much as 20 mm originally, was apparently trimmed at some point in order to fit the frame, but the gessoed area has remained pristine. Because of the buildup of paint around the edges of the gessoed area, the experts concluded that the reserve could not have been caused by a removal of paint or stripping of any part of the original masterwork.

has not been altered, and that the columns depicted in alleged copies of the original were added by the copyists themselves. In 2004-05 an international team of 39 specialists confirmed Kemp’s view after undertaking ‘the most thorough examination of the Mona Lisa ever’. They discovered that the frame covered an unpainted strip around all four edges of the panel, leaving the gessoed, or painted, portion untouched. The bare strip (called the ‘reserve’), which was likely to have been as much as 20 mm originally, was apparently trimmed at some point in order to fit the frame, but the gessoed area has remained pristine. Because of the buildup of paint around the edges of the gessoed area, the experts concluded that the reserve could not have been caused by a removal of paint or stripping of any part of the original masterwork.

Myth: The Mona Lisa is the most valuable painting in the world.

The lady shows her worth. The Mona Lisa is widely perceived as Leonardo’s greatest work, but not many critics agree. Those who are enraptured at the outset eventually grow weary of it, some even finding the subject “faintly repulsive.” More lasting respect is paid to The Last Supper, which is seen as a complex psychological panorama compressed in very limited space.

One would think the Mona Lisa has a financial worth matched only by its fame. In fact, Guinness lists the painting as the most valuable in the world, based on an assessment of $100 million in 1962. The honor is of dubious merit, however, since the appraisal was made for an insurance coverage that was never taken. As a practical matter, those that have gone through public auction—e.g., Van Gogh’s Irises, which sold for $53.9 million in 1987—are financially more valuable because of their proven market performance.

One would think the Mona Lisa has a financial worth matched only by its fame. In fact, Guinness lists the painting as the most valuable in the world, based on an assessment of $100 million in 1962. The honor is of dubious merit, however, since the appraisal was made for an insurance coverage that was never taken. As a practical matter, those that have gone through public auction—e.g., Van Gogh’s Irises, which sold for $53.9 million in 1987—are financially more valuable because of their proven market performance.

Moreover, the $100 million has already been surpassed in terms of actual dollar price by three other paintings: the Adele Bloch-Bauer I by Gustav Klimt, which was sold for $135 million (£73 million), the Woman III by Willem de Kooning, which sold for $137.5 million in November 2006, and No. 5, 1948 by Jackson Pollock, which sold for a record $140 million also in November 2006. The least that could be said for the Mona Lisa, however, is that until and unless it is decided to place this French-owned Italian classic on the bloc, its real value will never be known. If it is any consolation at all to the lady’s millions of admirers, $100 million in 1962 is approximately $670 million in 2006 when adjusted for inflation using the US Consumer Price Index.

And the billionaire connoisseur who is lucky enough to snag the Mona Lisa at $670 million will be getting himself a bargain—with a painting that, in the strictest sense, is not even an original! While he will be buying the piece that can be seen hanging proudly in the Louvre, he will be paying for the four versions of the item that Leonardo painted in succession, all co-existing with and inseparable from each other. Modern x-ray studies have shown that under the visible facade of the ‘Louvre ouvre’ are three more layers, each painted over by Leonardo because he wasn’t satisfied. The Mona Lisa that smiles mystically at the viewer these days is the maestro’s fourth and final rendering of the lady from Naples.

• All non-textual materials are from Google Images.

The smile becomes her. According to art historian Giorgio Vasari, who wrote in 1550, Leonardo’s model for the Mona Lisa could not bring herself to smile as the painter wanted. It was agreed to put her in the right mood by hiring musicians and jesters to perform while she was being painted. Aided by Leonardo’s coaxing and happy banter, the technique succeeded in eliciting the beautiful expression that graces the now celebrated painting.

The smile becomes her. According to art historian Giorgio Vasari, who wrote in 1550, Leonardo’s model for the Mona Lisa could not bring herself to smile as the painter wanted. It was agreed to put her in the right mood by hiring musicians and jesters to perform while she was being painted. Aided by Leonardo’s coaxing and happy banter, the technique succeeded in eliciting the beautiful expression that graces the now celebrated painting.  regard the beguiling smile on the Mona Lisa as a singular stroke that only someone like da Vinci could have fashioned. To them, it’s the “most perfect” part of the painting hands down (no pun intended).

regard the beguiling smile on the Mona Lisa as a singular stroke that only someone like da Vinci could have fashioned. To them, it’s the “most perfect” part of the painting hands down (no pun intended). Wanted: one very sharp eyebrow pencil. Mona Lisa’s face is criticized for being marred by an imperfection, caused by Leonardo’s alleged failure to paint eyebrows on his subject. Fortunately, art historians assure us that Mona Lisa was painted as she would have appeared in those days—with no eyebrows. Renaissance fashion in Florence called for ladies to shave them off, as they were considered unsightly. Some sources claim that, for modern viewers, the missing eyebrows add to the slightly semi-abstract quality of the face.

Wanted: one very sharp eyebrow pencil. Mona Lisa’s face is criticized for being marred by an imperfection, caused by Leonardo’s alleged failure to paint eyebrows on his subject. Fortunately, art historians assure us that Mona Lisa was painted as she would have appeared in those days—with no eyebrows. Renaissance fashion in Florence called for ladies to shave them off, as they were considered unsightly. Some sources claim that, for modern viewers, the missing eyebrows add to the slightly semi-abstract quality of the face. at the Louvre to say that Mona Lisa’s mouth and hand are not the only points of interest in the painting. Watch out for her eyes as well, because they have a knack of following you as you move around the room. Her gaze seems to be fixed on the observer wherever he is, as if to welcome him to some silent communication. The trick, however, is not unique to that painting, nor is it limited to the works of the masters. Any portrait that rests on a flat surface and has only two dimensions will give the same result. The eyes of a subject in such a portrait will give the illusion that they are looking at you from every angle, because they are just so many points fixed on a plane and will be precisely the same points seen at any angle they are viewed from. If the eyes are pictured or drawn as looking directly at you when you are in front, they will be seen looking at you when you move to either side; and if the eyes are represented as looking in some other direction the observer cannot place himself in a position so they will appear to look at him.

at the Louvre to say that Mona Lisa’s mouth and hand are not the only points of interest in the painting. Watch out for her eyes as well, because they have a knack of following you as you move around the room. Her gaze seems to be fixed on the observer wherever he is, as if to welcome him to some silent communication. The trick, however, is not unique to that painting, nor is it limited to the works of the masters. Any portrait that rests on a flat surface and has only two dimensions will give the same result. The eyes of a subject in such a portrait will give the illusion that they are looking at you from every angle, because they are just so many points fixed on a plane and will be precisely the same points seen at any angle they are viewed from. If the eyes are pictured or drawn as looking directly at you when you are in front, they will be seen looking at you when you move to either side; and if the eyes are represented as looking in some other direction the observer cannot place himself in a position so they will appear to look at him.  In the late 19th century, the Baedeker guide called it ‘the most celebrated work of Leonardo in the Louvre’; still, artists copied the Mona Lisa only half as many times as certain works by Murillo, da Correggio, Veronese, Titian, Greuze and Prud’hon. Not until the 20th century would it assume the ranking it has since enjoyed as the most famous painting in the world. But fame often breeds controversy, and in the case of the Mona Lisa, fame would bring almost every feature of this masterwork—from its name to the manner of its creation—under the speculative gaze of professionals and amateurs alike. Today what seems to be the only sure thing about the Mona Lisa is its authorship by Leonardo. In this essay are some popular traditions about Leonardo’s lady and the alternative theories and beliefs—many no less debatable—that may in time replace them.

In the late 19th century, the Baedeker guide called it ‘the most celebrated work of Leonardo in the Louvre’; still, artists copied the Mona Lisa only half as many times as certain works by Murillo, da Correggio, Veronese, Titian, Greuze and Prud’hon. Not until the 20th century would it assume the ranking it has since enjoyed as the most famous painting in the world. But fame often breeds controversy, and in the case of the Mona Lisa, fame would bring almost every feature of this masterwork—from its name to the manner of its creation—under the speculative gaze of professionals and amateurs alike. Today what seems to be the only sure thing about the Mona Lisa is its authorship by Leonardo. In this essay are some popular traditions about Leonardo’s lady and the alternative theories and beliefs—many no less debatable—that may in time replace them. rightly so, as this was the nickname of the lady who, we are told, sat for it. In professional circles, it is formally known by its descriptive title ‘Portrait of Lisa Gherardini, Wife of Francesco del Giocondo’.

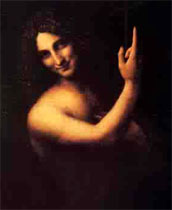

rightly so, as this was the nickname of the lady who, we are told, sat for it. In professional circles, it is formally known by its descriptive title ‘Portrait of Lisa Gherardini, Wife of Francesco del Giocondo’.  Cherchez l’homme! Some art historians have even gone beyond the gender barrier in their pursuit of the real Mona Lisa. Thus, it has been suggested that Leonardo’s mysterious poser was the same male model he used for St. John the Baptist, which shows an uncanny resemblance to La Gioconda. Another suggestion is based on an anonymous statement linking the Mona Lisa to an image of Francesco del Giocondo himself—perhaps the origin of the controversial idea that the Mona Lisa is the portrait of a man.

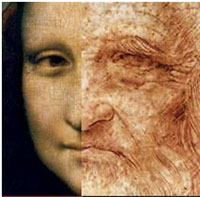

Cherchez l’homme! Some art historians have even gone beyond the gender barrier in their pursuit of the real Mona Lisa. Thus, it has been suggested that Leonardo’s mysterious poser was the same male model he used for St. John the Baptist, which shows an uncanny resemblance to La Gioconda. Another suggestion is based on an anonymous statement linking the Mona Lisa to an image of Francesco del Giocondo himself—perhaps the origin of the controversial idea that the Mona Lisa is the portrait of a man. the same person using the same style; (2) the drawing on which the comparison is based may not really be a self-portrait; (3) as Sigmund Freud surmised, the Mona Lisa depicts the artist’s mother Caterina, accounting for the resemblance between artist and subject, and further explaining why Leonardo kept the portrait with him wherever he traveled until his death; and (4) the resemblance is purely accidental. As Wikipedia puts it, being ‘an artist with a great interest in the human form, Leonardo would have spent a great deal of time studying and drawing the human face, and the face most often accessible to him was his own, making it likely that he would have the most experience with drawing his own features. The similarity in the features of the people depicted in the Mona Lisa and St. John the Baptist may have resulted from Leonardo’s familiarity with his own facial features, causing him to draw other faces in a similar light’.

the same person using the same style; (2) the drawing on which the comparison is based may not really be a self-portrait; (3) as Sigmund Freud surmised, the Mona Lisa depicts the artist’s mother Caterina, accounting for the resemblance between artist and subject, and further explaining why Leonardo kept the portrait with him wherever he traveled until his death; and (4) the resemblance is purely accidental. As Wikipedia puts it, being ‘an artist with a great interest in the human form, Leonardo would have spent a great deal of time studying and drawing the human face, and the face most often accessible to him was his own, making it likely that he would have the most experience with drawing his own features. The similarity in the features of the people depicted in the Mona Lisa and St. John the Baptist may have resulted from Leonardo’s familiarity with his own facial features, causing him to draw other faces in a similar light’.